MEMORIES OF MY TIME ON HMS MARTIN IN 1942

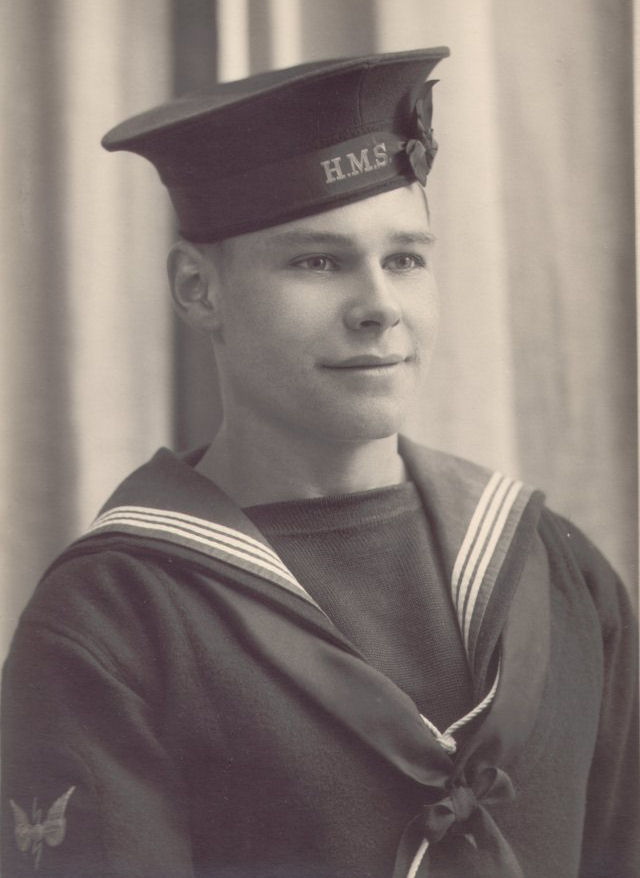

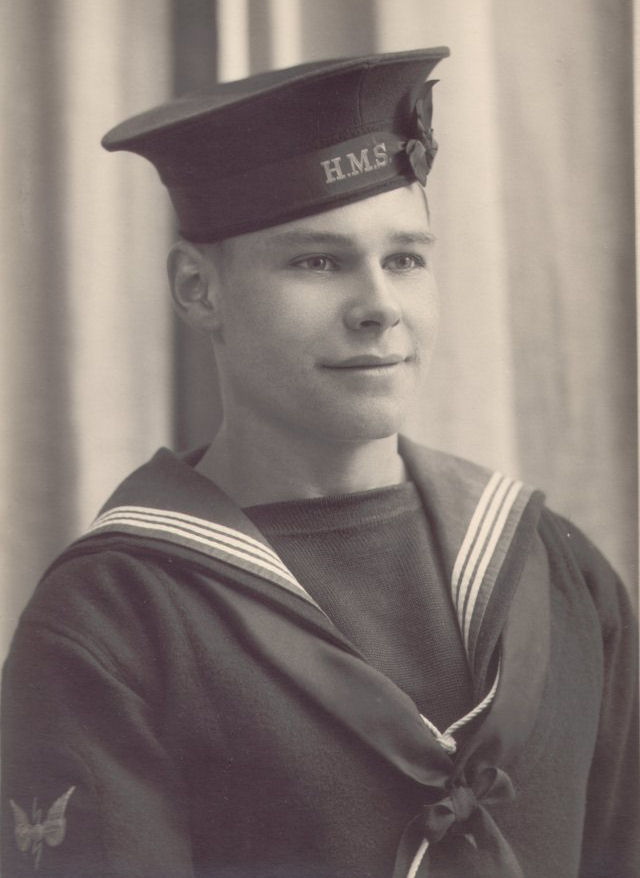

Written by “Gus Britton” C/JX 159905 in 1989

|

|

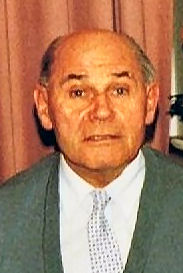

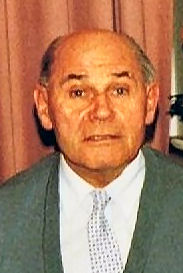

JOHN HENRY BRITTON |

|

1924-1992 |

|

I joined HMS Martin on the 25th March 1942 when she first commissioned at Vickers Armstrong shipyard at Walker on Tyne, near Newcastle. I was a newly qualified Leading Telegraphist, not quite 19 years old and Martin was to be my second ship, the first was Arethusa, a light Cruiser. The communications mess was right down forward in the bows of the ship and in it lived the “Bunting Tossers” (Signalmen), Sparkers (Telegraphists) and Coders, in all about 16 ratings. The mess was directly under “A” Gun Turret which was driven by a new design, very noisy, leaky and smelly oil pump system which occupied about one third of our already cramped mess space. I remember there were two or three stanchions in the mess and on each one at just below knee height was an electric open bar fire. Consequently everyone in the mess had burn holes in their trousers. Most of the mess members were “Hostilities Only” ratings and also on their first Destroyer so to them and me “Canteen Messing” was a new experience. For all cooked meals we had to prepare the food ourselves and then take it to the galley for the cooks to “Finish it off”. Many of us found we had culinary skills previously unknown. The earliest event I recall whilst at sea on the Martin was seeing the Battleship King George V ram and cut off the stern of the Destroyer Punjabi. I have since read that this was when we were acting as distant covering force for Russian Convoy PQ15 and occurred on the 1st May 1942, so it must have been during Martin’s first operational sortie after working up at Scapa Flow. I clearly remember seeing some of the Punjabi’s crew stepping from the front part of the ship into Martin’s boats which had been sent to rescue them. Punjabi’s Captain was on Martin’s bridge when an Aldis Lamp signal came from the Admiral on KGV saying sorry for the loss of his ship. When asked if he wished to reply, Punjabi’s Captain said yes, make “It’s a f…ing fine way to loose your shipmates”. I wonder if Martin’s Yeoman of Signals, Harry Plaice, remembers making that reply and if it is recorded in the enquiry report that must have been made after such a collision. I very soon learnt that when on Russian Convoys, never to take my clothes off. In late May, Martin joined its first convoy PQ16 as close escort. Everything was quiet and peaceful so I decided to take a shower. Whilst stripped off and soaking wet, action stations sounded and I found myself sitting in front of a wireless set in the W/T Office for quite a few hours, wrapped only in a towel, during which time the convoy was attacked by dive bombers, torpedo carring aircraft and U-Boats. We made a number of trips to Russia, not always with convoys. I have a vague memory of going ashore, I think in Archangel, and seeing wide streets with loudspeakers blaring out speech and music and groups of uniformed men and women marching from place to place. But my general impression, especially of Murmansk, was of a place of desolation and decay. At one time we were tied up one side of a jetty when a Russian Destroyer came in and tied up to the other side. Shortly afterwards what appeared to be the whole crew came ashore, fell in on the jetty and marched away. A new crew came marching down the jetty and went on board – but they were all women! Is my memory playing tricks or did this really happen? Martin was not with the next convoy, the infamous PQ17 but it did make

another two trips to North Russia with supplies and personnel, one in

July and the other in August. It was during the return journey in August

the Martin, in company with Marne and Onslaught intercepted the German

Minelayer ULM about 100 miles east of Bear Island and sank her. I remember

we stopped for a short while to pick up survivors and I personally helped

pull on board oil soaked Germans, one of whom said to me in English “Thank

you for saving my life”. One event that sticks in my mind, although I can’t remember when it happened, was when the Petty Officer Telegraphist Eggie Gent was granted a special leave for personal reasons. The Captain sent for me and if I would be able to run the W/T Office in Eggie’s absence. How proud I felt, being just 19, as I assured him that I could manage. My next memory is of an incident during PQ18. This was the first PQ Convoy to have an Aircraft Carrier with it, which made us all feel a little more confident that the air attacks would not be so violent. It was not to be! After one attack one of our aerials was down due to gun fire and I had to go out and repair it. I was standing on top of the R.D.F (Radar) cabin when all hell let loose as another attack started. I remember looking out over the port bow and seeing about thirty torpedo bombers flying low over the far side of the convoy. The noise of anti aircraft fire was deafening when suddenly it went perfectly quiet. I looked round and saw a massive cloud of black smoke. A merchant ship full of ammunition had been hit, the explosion temporarily making me deaf. I was during a Russian Convoy that I was told to keep watch on the frequency used by the enemy reconnaissance aircraft which used to patrol round the convoy and “Home in” the bombers and submarines. So far we had not been spotted when suddenly I heard an aircraft making sighting reports. Using the radio direction finder, I took bearings every time he transmitted and reported this up the voice pipe to the bridge. After about half an hour reporting to the bridge, I was told no further reports were necessary as the aircraft had been in sight, circling the convoy for the last twenty minutes. Just before one trip up north, two boffins came into the W/T Office with a massive sheet of plywood on which was fitted lots of electronic components including a cathode ray tube. They installed this in one corner of the office and operated it throughout the trip. It turned out to be an early “Breadboard” version of a panoramic receiver for detecting any transmissions over a broad frequency range. This helped in the detection of U-Boats. At the end of October 1942 we sailed south for the Allied Landings in North Africa. After a brief call at Gibraltar we sailed into the Mediterranean on the morning of the 7th November. I remember being very busy with paperwork adding amendments to the operational orders for “Operation Torch”. It was through doing this that I learnt what was going to happen, later our Captain broadcast to the ships company and explained our mission. He said that Force ‘H’ of which we were a part, was going to patrol 60 miles north of the African coast to prevent any interference with the landings by enemy surface craft and as this was most unlikely we would have a nice quiet time compared to our Russian Convoys. As we were in company with a large force, the P.O. Tel asked me to sleep in the W/T Office so that I could be readily at hand in case of any emergency. The force patrolled backwards and forwards everyday and although I know now there were some air attacks I don’t remember them. They must have been light compared to our previous experience on Russian Convoys. At 0200 GMT on the 10th November I woke up in the W/T Office to find the main lights out, but by the light of the automatic emergency lanterns and through the smoke that was being sucked in by the slowing down ventilation fans I could see the two telegraphists and the coder on watch standing up in front of their desks, looking at me on the floor. At this stage the ship began to list to Starboard. I shouted “Let’s get out” and made for the door. I got into the starboard passage where men were running towards the door leading into the upper deck by the break of the foc’sle on the starboard side. The door was clipped shut. All the time I could hear screaming. In the dim light of the emergency lanterns I saw someone coming up through the round hatch from the boiler room below. It was impossible to walk across the cross passage to the port door, the ship was already listing more that 45 degrees. I clambered along the bulkhead, dragging myself towards the port door and out onto the upper deck below one of the ships boats. I was fully clothed and had my lifebelt on but it was not inflated. I found myself sitting by the boat davits, on the ships side which by now was almost horizontal. I recall hearing the loud hiss of steam and looking round at the funnel and thinking to myself “This lots going to blow up any minute”. I started to blow up my lifebelt. The next thing I remember was being in the oily water and thinking “Keep your mouth closed”. I saw a carley float with men on it so I swam towards it. Somebody dragged me inboard and we sat there, looking at each others shining black faces. Of the other 21 ships in Force ‘H’ there wasn’t a sign. How long I was in the water or on the raft I have no idea. Somebody said “Here comes that bloody submarine” and we saw a dark shape looming up in the distance. It was the Destroyer Quentin sent back to look for survivors. I was hauled aboard onto the upper deck where my clothes were cut off with a seaman’s knife and thrown back into the sea. Next thing under the shower, trying to remove the oil fuel. Luckily I hadn’t swallowed any but to this day that smell always brings back bad memories. I was given some clothing; I can’t remember exactly what except that the roughness of the shirt and trousers remains in my mind. Whilst on Quentin I saw other survivors lying on the messdecks who were in a bad way after swallowing oil fuel. At the time it all seemed like a dream and then suddenly it dawned on me what had happened and I began to shake. I don’t recall being landed at Gibraltar but I do remember being told that we were going to be shipped back home. We all went down to the jetty and got into a boat to go out to a ship lying out on the mole. As the boat moved off an officer came running down the jetty and called the boat back. He read out the names of all the communications ratings. We had to get out of the boat as there was an order in force stopping V/S and W/T ratings from leaving the Med. without relief. I was the only W/T rating. I never saw any of the other survivors again. I was kitted out and sent up to the North Front W/T station to await drafting to another ship. Shortly afterwards an incident occurred that could easily have resulted in my being charged with striking an officer. I was sent to collect a new pay and identity book. A rather officious Paymaster Sub-Lieutenant started questioning me on how I had lost my book. I explained that it had gone down in the ship with the remainder of my worldly possessions. He started lecturing me that I should have carried the book at all times. He finally gave in when I told him that the clothes I was wearing when I was rescued were cut off and thrown back into the sea. One day whilst I was on the ‘Rock’ I was drafted to a Cruiser, whose name I forget, that was in the harbour. A jeep was sent up to transport me so I collected my kit and was just loading it onto the jeep when the sirens sounded indicating that rock blasting was to commence and no traffic was allowed to move. Sometime later the all clear sounded and I was driven down to the harbour in time to see the Cruiser sailing into the Med. I returned to North Front W/T Station where, round about xmas time I was at a party when a Warrant Telegraphist told a three badge Leading Tel. that his relief was arriving on a troopship due to dock shortly. Stripey said he didn’t want a relief, he’d got a cushy number on the Rock and that’s where he wanted to stay. I arranged with the Warrant Tel. that the new chap would act as my relief, allowing me out of the Med. And so early in 1943 I took passage in a Cruiser (I believe it was the Scylla) back home but on the way we were diverted into the Bay of Biscay to sink an enemy blockade runner trying to reach the French coast. It was during this incident, having nothing to do that I again had an attack of the shakes. On arrival in Chatham Barracks as a survivor I went through a shortened joining routine and was given 14 days leave. Approximately 6 months later, after having been over to the States to

pick up a brand new L.S.T. (Number 9),

|